The movie Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love drew me in, twice. An engrossing but discomforting movie that highlights Cohen’s hurtful behaviour towards his muse and lover, Marianne Ihlen and her apparent willingness to be walked over like a beautiful but dispensable kitchen rug.

Although one person’s version of a complicated relationship, the truth is that elements of it echo through many connections with the instant attraction that signals losing touch with reality; a special kind of insanity reserved for lovers in the first flush of relationship. Could be a classic romantic novel with an emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending until you realise there’s a twist in the tale.

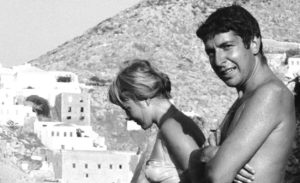

Marianne Ihlen met Leonard Cohen on the Greek island of Hydra in the 60’s, a place and time when what were seen as bourgeoise constraints on freedom were being thrown aside. Cohen was a charming man struggling to be a writer of substance. Ihlen was an engaging and nurturing woman, a mother at sea in an oppressive marriage.

They were together, on and off, until Cohen sidestepped into stardom, fuelled by lashings of drugs and sex with whoever was up for it. Marianne was left to face the harsh reality of being repeatedly dumped and then recycled when Cohen returned from ‘being obsessed with winning women’s favours’, which had become the most important thing in his life.

At this point, it’s tempting to pronounce judgement and offer my own tatty recipe for the perfect relationship, which is nothing more than an idealised projection of what I think might keep me safe and secure. I admit, I’m still scratching for wisdom here, which is a bit telling for a senior citizen, but I don’t think I’m alone in this vulnerable ignorance.

Growing up in the 60’s meant being influenced by the free love movement that, in part, challenged marriage as a form of enslavement for women. But what might have seemed a liberating ideal for women didn’t entirely ring true.

Many of us found that the love on offer was neither free, nor liberating because the same old patriarchal power dynamics that controlled sexuality and women’s bodies remained in place in politics, business, education and religion; everywhere really.

Neither was there much interest in exploring love and sex, other than from biological, psychological and evolutionary standpoints, all of which give us information but not much in the way of meaning, something that is central to spiritual development.

After my second go at the movie, this time with a friend, animated conversation broke out at dinner but we both struggled around the complications of relationship, particularly when it becomes sexual.

‘I suppose it’s the way of men,’ said my friend, unintentionally echoing Aviva Layton, friend of Leonard, who pronounced in the movie that, ‘poets do not make good husbands. You cannot own them. You cannot own a bit of them.’ She spoke with some authority having been married to poet Irving Layton, another serial womaniser.

Not content to leave it there, I enquired earnestly why we wouldn’t try to explore what love actually is and where it springs from, along with its erotic sexual companion, given that it seems to cause so much heartache. My friend wondered if I might be overthinking it.

Christianity, a religion that has much to say about love gets sexuality as muddled as anyone, especially when it over-literalises Augustine of Hippo’s idea that humans are massa peccati, or a mess of sin, which in the midst of the #Me Too movement is hard to ignore, but almost impossible to make a comeback from if we don’t dig a little deeper.

You could argue that Augustine is irrelevant given that he was born in 354 and part of the Christian church now embroiled in its own sexual crisis. But his questions arose from a deep love experience and struggling with desire that seemed both unmanageable and yet an integral part of his spirituality. They remain relevant today as we all wrestle with sexuality gone wrong; the resolution of which seems as out of reach as it was in Augustine’s time.

The focus these days is on having clear standards for sexual behaviour and safeguards that recognise power imbalances. To have consequences for actions, including punishments for people and organisations that contravene those standards. Whilst these approaches are important, understandings about what drives us still seems elusive if the social media floggings of ‘unredeemable sinners’ are anything to go by.

A complementary but challenging approach would be to recognise that the twists and turns of the romantic knife and the complexity of boundary crossing in sexual interactions are not so far removed from each other. Not driven so much out of our conscious, rational mind, although we’d like to believe this is so, instead arising out of the unconscious that is not much understood by us, yet.

Contemplating the idea that there are forces beyond our intellectual, evidence based way of understanding the world is not something we necessarily want to countenance. But it seems to me that unless we start to see our relationship and sexual problems in a more holistic and imaginative way, we’re refusing to look in the mirror to see that we’re all in this together.

Perhaps this is why transcendent and unconditional love is so crucial to religious traditions, notwithstanding the mess we make of it all, because that kind of love becomes real through human actions open to scrutiny, sustained across time and resplendent in its tender resilience through tough times. Sometimes, you could almost experience it as divine.

Thanks for your response, Sande.

This is an ideal. But you reach what you strive for. There are indeed many paths the expression of our sexuality could wander down. In the past, especially in my youth, the pursuit was for a satisfying orgasm, or possibly a relationship to provide them with regularity. The shallow emptiness that remains after a less than ideal pursuit, no longer interested me. Maybe the hormones have subsided and the closeness of death have been channeled into a desire for some foretaste of that heavenly realm where souls unite in transcendant bliss. This is what I asked the universe for in my shattered brokenness. So slowly, deliberately, in full consciousness and with consent deliberately discussed as it should be in thus age, rather than playing the normative seduction games, I have arrived at a relationship with dares to explore and express that sacramentality of our incarnated selves. Maybe in the haze of romance’s freshness, this is just an illusion that will fade with the passage of time into something less ambitious, proving this to be yet another delusion of the imagination. But I hope not, and am committed to its ongoing pursuit, feeling like I am just beginning to really explore this realm of the sacredness that sensuality can be.

Thanks Allan

Interesting idea that we reach for what we strive for and I suppose can only reach for what we think we know about. What we don’t remains invisible. So knowing more as we age makes sense from what you say and how wonderful that you’e got the opportunity to explore differently at this point in your life and maybe that’s when the unnown divine quality emerges from. I feel I know so little about it that I just have to go I don’t know.

But as always, I figure my tradition might have had something to say about it even although marginalised! So, was interested to read a piece from the ABC’s Religion and Ethics programme about the Song of Songs, so politely repressed across time by the church. https://www.abc.net.au/religion/poetry-sensuality-and-artistry-in-the-song-of-songs/11594800

The piece is drawn from a new book: The Song of Songs: A biography. Thought I might get it.

https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691146065/the-song-of-songs

I have of meditated on the divine sexuality of the Song of Solomon. It has been instrumental in my conceptual understanding, as have the tantric practices of Tibet. I look forward to reading your links. Thanks for the engaged duscussion. Shalom to you.

Sexual Love is a divine gift

Incarnate vulnerability

To be entered into with the same

Profound cautions one enters

The religious vocation

One makes love throughout

The entire day

A word, a touch, a glance

All moments of sacrificial offering

Of one’s soul as gift to the other

Thanks for this. My best response is to say that there certainly seems to be a continuum around sexual relationships. Perhaps from the sublime to the ridiculous and perhaps eveerything inbetween within one relationship, let alone several.

What you say sounds like an ultimate end of the continuum but I fail to see how it could be like this all the time. Is it an ideal? Something that some people yearn for and others don’t? Perhaps parts of this ideal could be how it is for some people, some of the time. I confess to inadequacy in this regard.