Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was hot news as I wandered into my favourite bookstore. Colleagues were offering opinions about President Putin’s actions, but other than thinking war is futile my understanding of the situation was limited. However, I was interested in the President’s close association with the Russian Orthodox Church and what that might mean.

As I scanned the new titles laid out on the big tables around the store my eye landed on a dull, sepia coloured book, In the Midst of Civilized Europe. An account of pogroms from 1918-1921 and the onset of the Holocaust. Instinctively, I reached out to pick it up.

I’d been reading about the Holocaust since I was 13 years old. My mum thought this was strange and perhaps it was. But I’d been immersed in Jewish biblical story with its overarching themes of suffering and separation since I was two weeks old. As an adopted person the themes of displacement called to me. My ongoing exploration had been lifelong, always drawn to the story of a people with whom I felt a strange affinity.

Turning the book over to read the back cover blurb, I was startled to find that the pogroms had been in Ukraine. In precise detail, author Jeffrey Veidlinger tells the story of violence that kept erupting from 1918-1921 when over a hundred thousand Jews were murdered. But it didn’t stop there. Veidlinger dragged me through unspeakable horror; burnings, mutilations, massacres and rapes, all within a chaotic political cauldron. This genocidal violence, says the author, ‘created the conditions for the Holocaust.’

This book takes effort. From trying to absorb the long and complex history of the region, sifting through an abundance of previously unknown characters through to the repetitive violence. I kept a map in my head to get a sense of scope and movement, then spoke aloud the names of the characters in the hope I could get a sense of them as real people. The techniques stopped me looking away and helped me cope by intellectualising what I was reading, which worked until I got to the last chapter.

Veidlinger says that in 1941 ‘the mass murder of Jews resumed in the days and weeks after the German invasion of the Soviet Union.’ In the first six months of war five hundred thousand Jews were killed. By the autumn of 1943 ‘the death toll approached 1.4 million, about a quarter of the total number of Jewish victims of the Holocaust.’ (p355) The vast majority had been murdered near their homes where neighbours watched and sometimes took part. The deadliest massacre was in Kyiv where ‘the Germans boasted of shooting 33,771 Jews over thirty-six hours.’ (p373)

I wept. Not a surfeit of emotion but a wordless lament, aware I was staring into the primal beast that lives just under the surface, in all of us. In response, a friend with whom I argue the toss about theology, suggested that sin and evil are real, but the cross is the sign that it has its limits. At the time it sounded liked irritating theological shorthand.

Part of my discomfort was because reports of Putin’s close relationship with Orthodox Christianity and Patriarch Kirill kept surfacing. In general, I knew that the Russian Church had been suppressed during the worst excesses of communism, but that things were supposedly different now. So different that the state, military, church, and God had cosied up in the Cathedral of the Armed Forces consecrated in 2020.

According to Bishop Stefan of Klin, ‘only a nation that loves God could build such a grand cathedral.’ He heads up the church’s department for cooperation with the army so I guess he can be forgiven for his wild enthusiasm but not everyone agrees with him. As Shane Walker reports in The Guardian, priests of the 70’s and 80’s who were targeted by the state cannot make sense of it whilst religious scholar Sergei Chapnin suggests this is about post-Soviet civil religion.

Putin considers he is engaged in a holy war destined to restore the ‘Holy Rus.’ This is the foundation of the Holy Russian Empire whose sacred mission is to preserve and expand Christianity under the double guidance of the tsar and the patriarch, according to Professor Jocelyne Cesari, on ABC’s Religion and Ethics Report. Ukraine is seen as part of this holy empire, which must be reunited, a view not necessarily shared by Ukrainians.

From a Western perspective a holy empire and associated war may seem preposterous. This from our valued secularist approach that ensures clear divisions between church and state, alongside plummeting adherence to Christianity. But perhaps it’s worth remembering Constantine.

In 312, Constantine was fighting Maxentius for control of the Roman Empire. As the story goes, Constantine had a dream or vision, which led to him claiming the protection of Christ over and above the old gods. The final battle was at the Milvian Bridge, just outside Rome. Constantine won, paving the way for Christianity to become the dominant religion of the Roman Empire and ultimately Europe. You could argue we’re at the tail end of that now.

For example, in my home country of Aotearoa, New Zealand, there is a tendency to think that religion, and in particular, Christianity, is over and done with. To some extent, statistics bear that out. But it’s much more complicated as Joe Grayland points out in his book, Catholics: Prayer, belief and diversity in a secular context.

Grayland argues that the reintroduction of pre-colonial indigenous prayer forms and spirituality has led to a blend of ‘secularised rationalism and sacralised indigenous expressions’, to the point where, ‘the Māori form of prayer, called a karakia, is the dominant public prayer form used for civic events, especially in government, health, education and public service contexts.’ (p17)

I’m not sure what the Pew Research Centre would make of this state sponsored approach to spiritual expression when they estimate that 84% of the world’s population is religious, although not necessarily signed up to a particular tradition. It is an evolving story.

Alongside this development, immigration enables some of the world’s religious to migrate to New Zealand bringing their varied traditions with them. Others become displaced people, arriving as refugees, bringing not only religion but significant trauma to add to the collective psyche of this place. For us to minimise the importance of this is to deny the different ways we lean into the ultimate mystery of being. It also enables a convenient forgetting of the role that Christianity played in the shaping of the Western world we inhabit.

Sometimes humans cope by a kind of forgetting because we do not want to see or cannot cope with the enormity of suffering. We become unconscious of the tragedy, trauma and wrongs that have been committed by ourselves and others. But if these things are not integrated, they seethe away under the surface and will eventually demand attention. Similarly, with collective memories and transgressions. Although there may be a cessation of hostilities, treaties signed, reparation paid, borders redrawn and multiple changes of power, what runs deep remains, despite eagerness to move on and forget.

Ukraine and Russia have hundreds of years of multi layered religious, cultural, and political history that is woven throughout narrative and memory both individual and collective, material, and instinctual. And despite all the commentary from knowledgeable people around the world, I suspect that no-one knows the outcome as unfolding history tends to be chaotic and unpredictable.

My reading of Veidlinger’s book and intentionally following some of its threads has allowed me an enlarged perspective whilst still being a naïve enquirer about it all. But, as always, the challenge is to reflect on how this engaged and interacted with my own life experiences. To notice what surfaced, what begged for attention and to sit with the tension of those things.

First up was my deep connection with Jewish story and second, the Christian narrative so subverted for their own ends by Constantine and Putin. The tension tightened with my friend’s comment, which irritated me enough to follow it through in my own instinctual way rather than exploring a theological text.

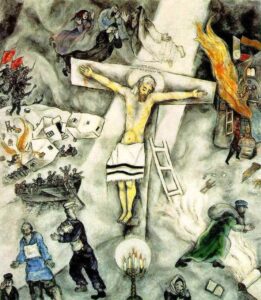

My exploring, although I’m unable to explain how I got there, took me to Marc Chagall’s White Crucifixion. Chagall presents Jesus crucified as a Jewish martyr, draped in a prayer shawl, and surrounded by images of Jewish persecution in the 1930’s, the deliberate targeting that was the prelude to the Holocaust. According to James Harris MD, the use of a Christian symbol was intended to alert a Christian audience to ‘the inhumane treatment of European Jews and to counteract the indifference to their plight.’

But whilst the cross is central to and synonymous with Christianity, its symbolism reaches further than one religion. As Carl Jung would have it, crucifixion is an archetypal motif associated with conflict and the problem of opposites. He held that ‘we all have to be crucified with Christ, that is, suspended in a moral suffering equivalent to veritable crucifixion.’ [i] Put like that this symbol can be understood by every human being.

This way of describing and understanding the sometimes incomprehensible experiences of life through universal symbols that, according to the Jungian world, arise from the collective unconscious, could be an important step in the evolution of religion and spirituality.

Certainly, some symbols are held as sacred, nurtured, worked through, and understood more fully by the traditions they are synonymous with. But when there is a universality about them, they seem to carry a primal power that draws and sometimes repels people. It’s no wonder that when symbols, and the rituals associated with them, are combined with state power, they have the potential to be used as instruments of control.

My experience of exploring Jungian ideas combined with dream analysis has activated considerable reflection about the hard edges of religious, cultural, and political institutions. An acceptance that whatever values they promote, power dynamics and the shadow are at play every day, but that’s not my problem. My job is to live with the tension of opposites that arise within me until there is a resolution, although it’s often not clear how that happens.

What is clear is that living in a symbolic way allows faith to develop beyond institutional beliefs, enabling engagement with the great mystery of being as it is revealed within me. That doesn’t mean it’s a free for all. Far from it. Living in and exploring the tension of opposites is an everyday challenge, which is aided by my lifelong immersion in the Judeo-Christian story that flows in and through me in a way I find difficult to explain. And it helps to have a theological buddy to be irritated by and argue the toss with.

Image: White Crucifixon, Marc Chagall, 1938

Also published on La Croix 26 April 2022

When sacred symbols and rituals are combined with state power

[i] Carl Jung, Collected Works Volume 12, Psychology and Alchemy, Paragraph 470

As always, I learn so much, my wonderful friend!! Miss you xxx

And you! Wondering about coming to hear you in June …

sustained excellence and so helpful Sande. More anon.

Thanks George. Look forward to your insights.

Fascinating as always.

Thanks Jude. Exhausting to write!