There’s a pyramid in Rome that presides over a frantic intersection, the kind that only Italians seem able to navigate without appearing suicidal. Like its Egyptian relatives, this pyramid is a portal to the underworld.

There’s a pyramid in Rome that presides over a frantic intersection, the kind that only Italians seem able to navigate without appearing suicidal. Like its Egyptian relatives, this pyramid is a portal to the underworld.

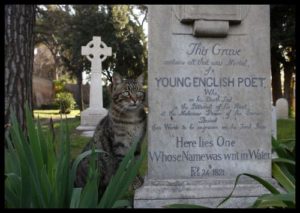

Spreading out from one of its angles is a tranquil cemetery where the English poet John Keats is buried, consumed by tuberculosis at just 25. Not far away lies Percy Shelley who once said of the cemetery that ‘it might make one in love with death, to be buried in so sweet a place.’ He had a point. This gathering of graves is a beautiful place to linger; strangely alive, dead ends softened by foliage and a collection of cats, an unexpected find on my pilgrimage to Rome.

A grave lies open in another garden; its emptiness the triumph of Easter but after a few hundred years of confusing science with mythology, this is a story hard to fathom. At face value, it promises eternal life, but this may be less than appealing if your current life is more than enough to deal with.

What has much more potential is the journey to the underworld that all ancient heroes seem to make. It’s intriguing that they travel in the prime of their lives, returning almost unrecognizable, able to transcend the usual stumbling blocks.

Plato included this underworld journey in his allegory of the cave, written about 400 years before Christianity. His story suggested that humans sit chained in the depths of a cave staring at reflections on a wall and mistaking that for real life. One of the cave dwellers is freed and dragged up to see the light of the sun. This hero realizes that he has been living in the dark, watching someone else’s life and mistaking it for his own reality. The sun enables him to see life as it really is and to continue living, this time with eyes wide open.

Myth, notes Richard Holloway, former Bishop of Edinburgh, is the narrative form of all religions, stories expressing but not explaining a universal human experience. Writing in his poignant memoir, Leaving Alexandria he points out that ‘the power of myth lies in its ability to represent ourselves to ourselves.’

When myth becomes embedded in the concrete world of religious dogma and misrepresents itself as the only story, it can become linear, flat and one dimensional, losing its ability to get under our skin where it belongs. At that point the slide into irrelevance beckons.

Death, its accompanying journey to the underworld and subsequent enlightenment can be relegated to our last days or we can be, like Shelley, a little in love with its transforming power through life.

However, that’s a much more challenging option as Plato’s hero found. On fire with his new life, he raced back to the cave to share the good news with his buddies. Sadly, the habits of a lifetime are hard to break. No-one wanted to hear.

Easy to check out, readable…heck I put to leave a commment!

Thanks!