The pounding of my heart, heralding a fear of who knows what had been completely quietened. In its place, an intense interest was flowering as I found myself peering deep into an empty chest cavity, tracking the embalmer who was trying to find an elusive artery severed too high by an over enthusiastic pathologist.

‘See, just there. Can you see it?’

‘Not really,’ leaning closer.

‘It’s bigger, thicker.’

‘Oh yes, yes, I see it now!’

Anthea went about her work with peaceful competence, gently introducing me to the art of preparing a dead human to be returned to the people who loved them. She picked up his arm. ‘See how massaging moves the fluid down the limb?’ How amazing. The colour under his fingernails was changing to that pale pink tinge more associated with living than dying.

Afterwards I wondered why on earth I’d picked up Ted’s hand, stroking it and talking to him. Not an intellectual conversation, more the kind of murmuring connection we have with our friends when they’re in trouble. Just being there, even though you know there’s nothing you can do for them that will make the least bit of difference.

In another part of the funeral director’s building Rena’s parents were distraught. Over the past week they’d traversed every emotion in the book. They found themselves celebrating the rapid arrival of Rena’s twin girls and then catapulted into cavernous despair as Rena inexplicably lost her grip on life.

The emotional tenor had changed when I went to help dress Rena for her trip home. ‘Well, it’s not going to fit, is it?’ said a friend, baldly stating the obvious to help us get a grip on reality. The soft cream wedding dress was made for a woman who’d been working out at the gym in anticipation of the big day, not for a woman who’d just given birth.

The gorgeous lace knickers were fine. One of Rena’s friends helped slide them on. A sheet preserved her dignity, as necessary in death as in life. But we came to grief over the bustier. Breasts getting ready to feed babies do not lend themselves to delicate little under things.

This struggle to try and make the lingerie fit, when it clearly wouldn’t, broke down some of the barriers about touching a dead person. Barriers about talking and laughing with and about this much-loved person. We all had opinions about how the dress could be rearranged to cover the autopsy scar. Then we realised it didn’t matter if we left the back zip undone. No one would be any the wiser.

‘What about the gloves?’

‘No, Rena has beautiful fingers and nails. Let’s leave the gloves off.’

‘But look at these marks where the IV lines have been. She’d hate to be seen like that.’

Have you ever tried to put full-length gloves on a dead person? It’s not for the faint hearted. Remember how difficult it was when you were little, and all those tiny channels wouldn’t fit over the muddled mess of fingers lost somewhere inside the glove? Multiply that many times and you’ll have an appreciation of the struggle. We finally managed and Rena’s mum scrunched them up at the elbows to give them a more authentic look.

As the loving work progressed, the stories started. Memories of Rena that turned and twisted through the laughter and the tears, braiding up the emotions into one enveloping, yet invigorating fabric of grief.

‘What about that line thing she always had around her lips?’ said Brent, Rena’s husband. We struggled to find the right lipliner. Nothing was quite right. ‘It’s ok,’ called back one friend as she left the room, ‘I’ve got just the right colour in the car.’ Eventually it was done. Her face. Just as she would have done her makeup. Important how we face the world, even in death.

We sped along the highway behind Brent’s car, taking Rena on her last ride home. ‘Pity about the stairs,’ said Rachelle the funeral director, as we looked at each other trying to work out how to get Rena up them with some dignity. We managed it, just.

‘You can talk to her ya know. She won’t wake up,’ announced Jay, Rena’s four-year-old to her pint-sized friend who didn’t look convinced. ‘See, I can touch her and everything,’ said Jay, still failing to draw her friend into conversation with Rena who was lying in her usual place on the couch.

All of us adults communicated our grown up knowing of loss through identical glistening eyes as the two kids bounced off to play, their interest waning in a mum who couldn’t respond to their effervescent conversation. We left Rena to spend the weekend with her family and friends.

The love that had threaded through that weekend was much in evidence when we arrived on the day of the funeral. Cards and drawings from the kids were stuffed down the sides of the couch. Soft toys and mementos peered over the top on a kind of lopsided sentry duty and flowers, wilting now, scattered over Rena as though they had fallen from some celestial flower barrow.

‘One, two, three,’ coached Rachelle, as we lifted Rena into her casket for the journey to her funeral. This time those dreaded stairs were managed by the addition of some brawny blokes. Moving dead people has a peculiar tension between keeping things seemly and the reality of physics. Rachelle had an adroit ability to keep that tension well balanced.

They just kept pouring into the funeral. Tragedy has a way of drawing people into itself in a way that nothing else in life does. The Diana syndrome I suppose. A young, brilliant life light, doused, before it had time to flame into its ultimate brilliance. And they mourned. For Rena, for her family, for themselves, for the incomprehensibility of life and please God, don’t let it happen to me or mine.

It was an idyllic outdoor setting, looking down on a small lake that nestled into the rolling countryside. Fitting for Rena, whose riding boots, saddle, and surfboard were arranged by the huge logs where we laid her.

They didn’t want to let her go. Flowers for the journey kept piling into the casket to keep company with the lipsticks and perfume we had packed in her small swing bag. As we women had agreed, no woman can leave home without these necessities.

The grief and loss were palpable. It had been the same the week before when we had taken Irena away. She had been 20 years older, in that energetic part of life when we know who the hell we are and are living ourselves out with intensity unknown to the young. That was a tragedy too, prompting hundreds to pour into the community centre to mourn and wonder.

Irena had known she was to die. Her friends had been with her through the months of illness, had made her casket and managed the celebration of her life both before, and after death. Like the families and friends of Rena and Ted, these people were actively involved in the death rites of a person they loved.

The days before we buried Ted had been busy as we moved him back and forth from home to church many times in the tradition of his people. Involvement and activity were integral to the grieving process of this family. But as Ted’s friends filled in his grave, I couldn’t help but think back to when I’d first met him.

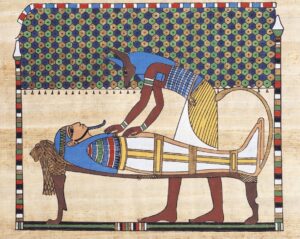

Anthea had been snipping through the sutures holding the huge Y incision that, our partly macabre obsession with television cop shows has taught us, denotes an autopsy. She peeled back the flaps and lifted out the bag of body organs that had been sliced and weighed by the pathologists, as they had set about determining the cause of death. Ted had drowned while out fishing to supplement the family budget.

My fears of fainting, or worse, throwing up in the embalming room hadn’t been realised. Instead, I was completely thrown by one simple procedure. In an autopsy, the brain is examined along with other body organs. To get access, an incision is made around the base of the head, allowing the flesh to be pushed forward exposing the skull. An embalmer must repeat the process to complete their work, with the result that, for a time, the face completely disappears.

At that moment, I suddenly understood much, much more about ‘face’. Why I hate going out without mascara twirled through my lashes and lipstick swept across my mouth. Why I can never remember the colour of my lovers’ eyes, only the shape of their face. Why facing up is so important and why staring people intently in the face can be so rude. Why the destruction of face in some cultures causes shame, sometimes to the point of death.

For face is where it all happens for us. Where joy and sorrow transform its shape in such radically different ways. Where anger floods the skin with boiling blood and pleasure softens and blurs our features. Where the gaze of a lover lingers, and the grimace of a killer can terrify. Where acceptance or rejection of the ‘other’ turns the face, this way or that.

For Ted to lose his face took him away from me. I felt a rush of relief as Anthea finished her work and his face reappeared. He was back, A person again. Yes, I can hear you. You want to tell me he was dead, right? Not there at all, just an empty shell? I beg to differ.

As I gazed into Ted’s face, held his hand, and gazed inside his body, I became part of his journey of death that few people will experience. By looking at him and touching him, I allowed myself to be connected to his life.

I knew he was a person who had loved and been loved. That there were things he was proud of and things he would rather forget. Tasks completed, some left undone. This body had held his hopes and dreams and given life to children. I didn’t know if he’d been a good person or a scoundrel. That was neither here nor there. What I did know is that he remained a person. Even in death, part of the rhythm of life.

Dead people have identities, which have not disappeared because they are dead. They have a right to be spoken to, to be called by their name, to be touched as a person. That’s not something that I thought about before I was on placement with a funeral director. And as a person who avoids touch in life, I’d been bewildered by the need, almost the compulsion to touch and interact with the dead people around me. What on earth was going on?

My growing understanding is that those few fraught days between a person dying and being returned to the universe from where they have come, are as pivotal to the lifecycle as the time in the uterus is. Whilst we can relate to our unborn children in the uterus, we know that the relationship is a very different one once they are born.

Before birth, we cannot see them, apart from the intervention of modern scanning technology. We cannot directly touch them or engage with the range of emotions that pass across their face. In some ways, we are relating to our unborn children with a mixture of hope and expectation, engaging with them in an almost spiritual sense.

At the other end of life, those of us left living must enter a different kind of relationship with our dead. We move from being able to touch, see, feel, and interact with one another, to a place where engagement is through memory, sense, and by the telling of stories that through the passage of time, become the myths of community that sustain us and future generations. But how do we get to that other relationship?

In Western society it seems that we’ve created a wide death gap by combining ‘other world’ theology that promotes the life of the soul over the body, with centuries long sanitisation of death rites. Through our abhorrence of physical and spiritual death, we have effectively colluded in our disempowerment around death and perhaps inadvertently contributed to the unhelpful dualisms of body/soul, heaven/earth and ultimately God/humanity.

Everything that I have seen, experienced, touched and felt on this placement screams out that there is a spiritual transitional role which we have either not noticed, been embarrassed about or actively turned away from.

Priests and ministers of all religions have long had a role in working with families to create funeral services, remembrances, and celebrations of life. Over recent years funeral celebrants have joined them in this work. In addition to this, some priests and a smattering of funeral directors offer grief counselling.

However, the care of the dead person, as they walk the road between death and committal to the elements, is largely left in the hands of funeral directors. This is not a criticism of the care that is given. The firm I worked with show great professionalism and care of the people with whom they are entrusted.

Rather, I want to suggest that the role of the priest is to not just be with the dying and the grieving but to also walk in the Valley of the Dead. To facilitate a positive connection between the living and the dead. To encourage the living to touch, to hold their loved ones. To ensure that the tears of the living are free to fall on the faces of the dead.

For there is healing in that touch, a growing understanding of the rhythm of life. As the living hold and do ordinary things for the dead person they love, small steps are being made from one kind of relationship to the other.

I’ve found that walking the Valley of the Dead is a strangely life enhancing experience. Where the relationship between the living and the dead becomes blurred. Where we say goodbye to the body and start to let the new, spiritual relationship unfold. Perhaps that’s how the idea of resurrection gains life, as the dead begin to live again in the memories, language, stories, and conversation of their loved ones.

With thanks to ‘Rena, Ted and Irena’ and Davis Funeral Services for teaching me a great deal in December 2000.

All names and situations have been altered to protect privacy.

Postscript in January 2022

21 years have passed since I wrote this piece at the end of my first year of theological training. Much has happened in my life since then but strangely, I’m still interested in this intersection of life and death.

In those years I’ve led countless funerals. A few weeks ago, I got to the point of wanting to give them up. As a result, I began writing Funerals and our shared mortality and suddenly remembered that I’d been on this placement and written this reflection.

In 2022, Aotearoa New Zealand has become more secular. The funeral industry now largely controls the after-death process, adding funerals to the business of embalming, cremation, and burial to the point that very few funerals are held in churches anymore. A result of funeral directors being first on the scene and hearing people say, ‘we’re not religious’ without exploring what that means.

Secular funerals seem to suit many, but I wonder if it’s just another death-defying technique and that COVID could help us reflect more constructively on our shared mortality.

One Reply to “Walking the valley of the dead”