When Meghan and Harry headlined on Oprah about their struggles in the royal enclosure, it was like stepping into the Garden of Eden. The never-ending story of needing to grow into a new reality. Although the furore around the Duke and Duchess of Sussex shifted focus, my interest in Eden remained piqued.

In the original story, God was full of instructions. Do this, don’t do that. As though, thought Eve, that she and Adam had no ability to think for themselves. ‘It’s not the thinking they’re afraid of,’ said a voice that seemed to be coming from the Tree of Knowledge Eve was sitting under but forbidden to eat from. Startled to hear someone other than Adam or God, she looked up not sure whether to be frightened or delighted.

Uncurling itself from the branches was a beautiful shimmering snake, resplendent with lustrous colours and intricate patterns. ‘Who are you?’ asked Eve, by now a little confused, as the snake gently wound itself around her outstretched arm.

‘Some people see me as a goddess ruling earth, water and air. The nurturing feminine divine if you like. Mistress of live-giving cosmic forces. Others know me as Lilith, Adam’s first wife.’ Eve gulped, eyes wide as the snake continued. ‘But the Egyptians call me Renenutet because for them I’m the nurse who took care of pharaoh from birth to death.’

Eve felt as though life had just been turned upside down and inside out. The Garden had always been straightforward and ordered. A place and time for everything and everything in its place, including her. Now this. But somehow it fitted with how she’d been feeling. As though something in this garden wasn’t quite right. Was a bit off-kilter.

Being created from Adam’s rib gave her a magnificent sense of connection. No question. But she’d begun to wonder how things might be different if he’d been crafted from her rib. Every time she tried to talk about this and how God could only see things from his perspective, Adam shut her down. He said she was meant to be grateful and follow the rules, which were for her own good and thought out by minds greater than hers.

Unsurprisingly, this had led to some conflict between them. But, up until now, Eve hadn’t been able to figure out what to do. Meeting the snake had activated something. A sense, a feeling, a knowing that there had to be more than the Garden. Even if wanting that meant she was disobedient and even a little bit dangerous and exciting. Eve had trouble finding words for what was going on inside of her but instinctively knew she had to trust the snake.

You could argue that it all ended in tears. Eve convinced Adam there could be another way, which led to them both being thrown out of the family home to fend for themselves. Over time, Eve and the snake were labelled evil and sinful, a belief that has contributed to women being embedded as problematic in the Judeo-Christian tradition. For some people that won’t matter and can help them leave a religion they consider outdated and unnecessary. For others, this dissonance can prompt an existential struggle.

Living out of these deeply embedded biblical stories formed my psyche and cultural environment in ways that that go beyond religion, any belief system or family structure. Being alienated from them by moving away from organised religion created a chasm for me. A separation from my mother tongue that carries language, metaphor and symbols connecting me beyond time and into the collective unconscious.

As Murray Stein says in his foreword to The Bible as Dream: A Jungian Interpretation, the characters were like my own kin who ‘did not seem strange or distant people, historically or culturally’. (p12) Being adopted, unclear about genetic heritage or family ties and uncertain whether this mattered, or not, intensified the situation for me.

Understanding the importance of the separation took time. Once it dawned, I realised that re-engagement with these stories would help me explore my cultural and spiritual identity. But because many authorised interpretations of the stories landed in me with a dull thud, I had to find another doorway. This has meant utilising my imaginative intuition as well as incorporating my understanding of theology and biblical studies. Integrating them if you like, just as I’ve been doing with my life through Jungian dream analysis.

Central to this is how I read the bible. For instance, I don’t think anything in it is accidental. By that, I don’t mean that it should be read literally, although I recognise some people do this. Nor do I think it’s historically accurate, or the whole truth for all time. What I mean is that the writers were inspired in their own ways within their own context, imaginatively alive to the art or alchemy of writing.

Writers are often mystified about where their words, images, connections, and combinations come from. We can find ourselves in service to what some people call a muse. A form of inspiration that arises unconsciously and is often expressed through metaphor or symbol. Although editors will shape and form text in practical and conscious ways, they also have an instinctual element to their work, which takes us back to the snake.

In my re-creation of the story, I used three ‘unauthorised’ snake references from the multitude available, which enabled me to begin playing with the Garden of Eden. This symbolic approach allows the snake to appear feminine, nurturing, and life-giving. A significantly different image from the one that’s been dominant for thousands of years. That’s liberating.

Joseph Campbell, famous for his work in comparative mythology and religion, regarded the snake and eagle as timeless symbols. Whilst the snake is tied to the earth, the eagle soars through the heavens. The tension of those two opposites is resolved in the mythological fusion of the winged dragon. A creature able to rise spiritually but also be soulfully grounded and one that appears repeatedly in the bible.

Carl Jung suggested that the circular snake image, the ouroboros, symbolised the integration and assimilation of the opposites. A feedback system arising from living with the tension of opposites that brings the challenge to integrate our shadow side. An ongoing pattern of rebirth. Not in a literal, physical way but as part of inner, spiritual work.

So, the snake, a symbol pregnant with feminine, nurturing and healing properties in the ancient world, enters Eden. From this perspective, the snake is essential to Eve’s earthiness and provides an impetus to live out of her instinctual self. Whereas Adam appears to be tied into male authority and a slave to the intellect. Neither is good nor bad. Instead, a tension of opposites that must eventually be resolved. And it might well be, but that’s another snake story for another time.

Engaging with the bible this way is called the reader response method that contains two main ideas. The first is that the meaning does not reside within the text in a self-contained box but is actualised or created by the interaction of the reader and the text. Secondly, that the meaning of the text can differ from reader to reader. No one size fits all.

For some people this is difficult to deal with, especially if the bible is seen as a sacred text that cannot be tampered with. But tampering is exactly what’s been going on through the search to figure out when these ancient texts might have been written, by whom and then by hazarding an opinion about what they might mean.

As that valuable work turns into theology, that is, thinking about God, it can become dogmatic and lead to the symbolic and metaphorical elements of the stories being diminished. Then the stories start looking as though they are owned by a particular group, of which only a few are authorised to tell us what they think they mean.

From a literary perspective this makes little sense because once a piece of writing is complete, the creator must set it free so that the word can be received, lived in, and interpreted by the reader. Unless this is done, the story flatlines on the page, not for resuscitation.

Bible stories need the same freedom to suck in oxygen. Otherwise, they lose the ability to offer their multi-layered truth into our secularised, scientific world. The strange thing is that engaging symbolically, using imagination and instinct may be exactly how the original authors thought their stories would be read. After all, they wrote in times when dreams and visions were valued, not dismissed as fantasy or psychotic episodes.

A great deal of venom has been directed at Meghan and Harry for upsetting the royal apple cart. Some say they’ll need a thick skin, but I wonder if what will be needed more will be the ability to keep rebirthing. To be able to shed their skin time and time again as they outgrow what was, in the light of new instinctual understandings.

To meet and engage with the snake is to be blessed if we can use the experience to integrate instinct and intellect. But there’s also loss when that means we stand in our own truth, outside any group that claims to know and hold it for us.

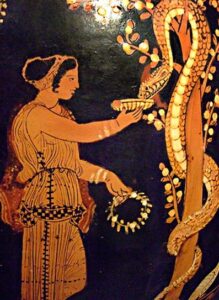

Image: From an Oil Jar (lekythos) illustrating the Garden of the Hesperides, a Greek myth that has interesting similarities to the Garden of Eden. The jar is terracotta made in Paestum South Italy 350-340 BCE.

Brilliant, Sande! I knew of Lilith, Adam’s first wife, and have written about her – I have to explore more the connection with the serpent, about which I know little to nothing.

Easter Season Blessings

Bosco

Thanks Bosco.

I’ve set my self a tiny little challenge to see if I can hear the silent voices in the text and write what I hear. Might take a while because there are plenty of women with something to say in all those very thin pages!